The Future of Software

What's changed?

Software 1.0

A revolution in software has begun, and it will forever change the way we interact with computers. In fact, it will change our very notion of what computers are and what they can do. We are moving from a world of rigid, procedural software to a world of fluid, creative software powered by artificial intelligence.

We are moving from Software 1.0 to Software 2.0.

I’m stealing these terms from Andrej Karpathy, Open AI co-founder and legendary AI researcher. He first wrote about the two eras of software in his 2017 essay, describing Software 1.0 as follows:

The “classical stack” of Software 1.0 is what we’re all familiar with — it is written in languages such as Python, C++, etc. It consists of explicit instructions to the computer written by a programmer.

This describes most of the software you’ve ever used in your life. Some human writes highly specific, unambiguous instructions (computer code), and the computer follows those instructions to a T.

Software 1.0’s defining characteristic is its rigidity. Given the same inputs, it always produces the same outputs. It also takes its instructions very literally. For example, if you fat finger a formula in Microsoft Excel (the epitome of Software 1.0) it will not try to guess what you meant.

But rigidity isn’t a bad thing. In many applications, rigidity is a feature, not a bug. In domains like, tax, accounting, payment processing, e-commerce, and payroll, you want your software to be 100% rigid and deterministic. No one wants their payment processor taking any creative liberties.

For these domains, Software 1.0 has been a perfect fit. It helps us impose structure and order on a fundamentally messy and unstructured world. So it’s no wonder Software 1.0 powers so much of the world around us. Your email client, your calendar, your spreadsheets, your company's CRM — it’s all Software 1.0.

Software 1.0 is great if you need to balance a checkbook or solve an equation, but it can’t do everything. It struggles with many tasks that any human child can do, like recognizing someone's face or detecting someone's emotions by the tone of their voice. And it certainly can’t do anything creative, like writing an article or drawing a picture. Nor is it capable of reasoning or planning.

For these capabilities, we turn to Software 2.0.

Software 2.0

Most people call Software 2.0 “artificial intelligence”, but it’s important to remember that AI is just a new type of software.

Whereas Software 1.0 is defined by computer code, Software 2.0 is defined by the learned parameters of an artificial neural network. From Karpathy’s essay:

In contrast, Software 2.0 is written in much more abstract, human unfriendly language, such as the weights of a neural network. No human is involved in writing this code because there are a lot of weights (typical networks might have millions), and coding directly in weights is kind of hard (I tried).

The core idea behind Software 2.0 is that instead of writing explicit instructions, we instead allow a neural network to learn how to perform a task by exposing it to huge quantities of data. This gives Software 2.0 the ability to perform fluid, creative tasks that can’t be solved with Software 1.0.

The idea of the neural network had been around for decades, but until recently it didn’t work well in practice. This began to change in the 2010s, as big companies like Google and Facebook began investing more in deep learning for their search and recommendation algorithms. Suddenly neural networks started working very well, and we saw a series of breakthroughs in computer vision and language processing.

But of course, it was ChatGPT that thrust AI into the public consciousness and catalyzed the Software 2.0 revolution. ChatGPT, the epitome of Software 2.0, established LLMs as a powerful, general purpose model architecture that could be used to build a variety of different applications.

If Software 1.0 is defined by its rigidity, Software 2.0 is defined by its fluidity. Software 2.0 doesn’t take its instructions so literally. You can tell it what you want in natural language, and it won’t be angry if your request had a few typos.

Software 2.0 is non-deterministic. If you ask ChatGPT the same question twice, it might give you two different answers. And it’s remarkably creative. Software 2.0 can generate poems, articles, advice, and stunning images.

Perhaps most importantly, Software 2.0 can act as a general purpose reasoning engine. Unlike Software 1.0, it can perform tasks that it has not been explicitly programmed to perform. It can think creatively and make inferences the way that humans can. The importance of this can’t be overstated. It will change everything.

| Software 1.0 | Software 2.0 |

|---|---|

| Left Brain | Right Brain |

| Deterministic | Probabilistic |

| Objective | Subjective |

| MS Excel | ChatGPT |

| Adobe Photoshop | Stable Diffusion |

| Math and Logic | Language and Images |

| CPU | GPU |

A summary of the differences between Software 1.0 and 2.0.

What will software 2.0 look like?

If you've used ChatGPT you have a glimpse of what the future looks like, but only a glimpse. In fact, we will look back at today's AI Assistants and find them extremely primitive and limited.

I believe the software of the future be defined by five key developments:

- Tools: The ability to interact with existing Software 1.0 infrastructure.

- Agents: The ability to autonomously perform tasks, using tools and other techniques.

- Humans in the Loop: The ability for human supervisors to direct this process.

- Memory: The ability to recall and learn from previous interactions and tasks.

- Just Plain Smarter: Self explanatory.

Let’s discuss each in depth.

Tools

Software 1.0 isn't going anywhere. Some people make the mistake of thinking that Software 1.0 is just a poor facsimile of Software 2.0, but it’s really not. While there are some applications where Software 2.0 might simply replace Software 1.0 altogether (like customer service chatbots), for the most part they simply serve different purposes and will coexist.

Therefore Software 2.0 will need an interface to Software 1.0. We call these tools.

Examples of tools might include…

- Searching the web

- Looking up the price of a product or stock

- Adding an event to the calendar

- Adding a new employee to a database

- Writing and executing code

Humans perform these tasks by using a mouse, keyboard, and graphical user interface. But these modalities don’t work so well for LLMs, at least not right now.

Instead, LLMs currently use tools by emitting special tokens that indicate that the model wants to use some predefined tool. Then, the rest of the program parses the input and executes that "tool call" and returns some result to the LLM. Usually this takes the form of an API call to another system, which means that the other system must expose an API that the LLM is allowed to use.

But what if there is no API? What if there is no way to programmatically interact with the application? Some apps — like Google Search — don't actually want other programs to be able to interact with them. They only want humans to interact with them, so they only expose a UI, not an API.

Therefore an active area of research is giving LLMs the ability to interact with user interfaces, not just APIs. These are sometimes called large action models, and with the help of computer vision, they enhance LLMs with the ability to click buttons, type in text boxes, and perform other actions that a human can perform in a user interface.

While this area is promising and would unlock many capabilities for LLMs, it's not clear which approach will win out — APIs or UIs. If an application does expose an API, it sure is a lot easier for the LLM to just use that. LLMs already understand text-based APIs perfectly well today, and this type of tool usage already works very well in current LLMs.

But if LLMs could also seamlessly navigate any web page or mobile application the way a human can, this would undoubtedly be a big unlock. To use a metaphor, it would mean LLMs could walk in the same door that the humans walk in, and we wouldn’t have to build any new doors off to the side for them to use.

Personally, I'm betting on text-based tool usage because of its simplicity and reliability. But I am also open to the possibility that large action models might soon provide a viable alternative for applications that don't expose an API.

What I can say for certain is that tool usage is here to stay and will be a critical part of Software 2.0 applications in the future. An AI assistant that can’t actually do anything on your behalf isn’t very useful. But an assistant with read/write access to your calendar, your spreadsheets, your CRM, your expense management software — that’s very useful.

Tools give us the best of both worlds — combining Software 1.0's rigid reliability with Software 2.0's fluid flexibility. Like mixing chocolate and peanut butter, the result is greater than the sum of its parts.

Agents

Agents are LLM assistants that do things autonomously, without being prompted. ChatGPT doesn't do this, of course. It only speaks when spoken to. (At least that’s true as I’m writing this in May 2024. Rumors are constantly circulating about Open AI’s plans to make ChatGPT more agentic.)

But at least for now, ChatGPT is not very autonomous. You send it a message, and it responds back. This means it’s very limited in its ability to perform complex, multi-step tasks that require iteration and feedback from the real world, like planning a vacation or crafting a new marketing campaign.

Agents go beyond the message-in-message-out paradigm and enhance AI assistants with the ability to decompose problems into smaller steps, perform actions in the real world, and continually perform actions until the job is done.

Some people refer to non-autonomous assistants like ChatGPT as copilots. Copilots simply provide one answer at a time, whereas agents can perform complex, multi-step tasks. In reality this distinction is more of a spectrum. Many Software 2.0 applications that today look like copilots will gradually become agentic in the future.

In a recent talk, Andrew Ng, leading AI researcher and founder of Google Brain, outlined three important design patterns for agents (in addition to tool usage, which we’ve already covered):

- Reflection: The ability to periodically reflect on whether the job is completed or the agent’s work is satisfactory. (I know a few humans who could really use this skill.)

- Planning: The ability to decompose a big problem into smaller steps.

- Multi-agent Collaboration: Delegating different aspects of a problem to different AI assistants with different roles.

In our work at Quotient, we leverage all three of these techniques, and in fact multi-agent collaboration is foundational to our agent framework.

One purpose multi-agent collaboration serves is essentially a form of reflection, where one agent does something (like writing a blog post) and another agent critiques its work.

But another, perhaps more important purpose it serves is that it allows the agents to have different sets of knowledge and tools. For example, you might have one agent in charge of writing an article and another in charge of creating the imagery for the article.

The first agent needs to have a lot of guidelines about how articles are supposed to be written — how long they are supposed to be, the tone they should employ, etc. But the second agent has a totally different job. It needs access to image-related tools, like the ability to generate an image with a diffusion model, the ability to overlay text on the image, etc.

I’ve found that agents are very much like human employees in this respect. No single human can possibly have all of the information and expertise needed to run an entire company, so we divide responsibilities and disperse knowledge across different departments.

Just as human employees begin to struggle as their responsibilities grow too diverse, so do LLMs begin to struggle the more tools and data are shoved into their limited context windows.

Tools, reflection, planning, and multi-agent collaboration will all help us build better agentic Software 2.0 systems. But there is one feature that agentic systems absolutely cannot function without.

Humans in the Loop

To build an agentic system that actually works in the real world, there must be a human in the loop. LLMs are simply not ready to do complex, long-running tasks by themselves. They need human supervision. They need to be able to take human feedback into account, and they also need to know when to proactively solicit it.

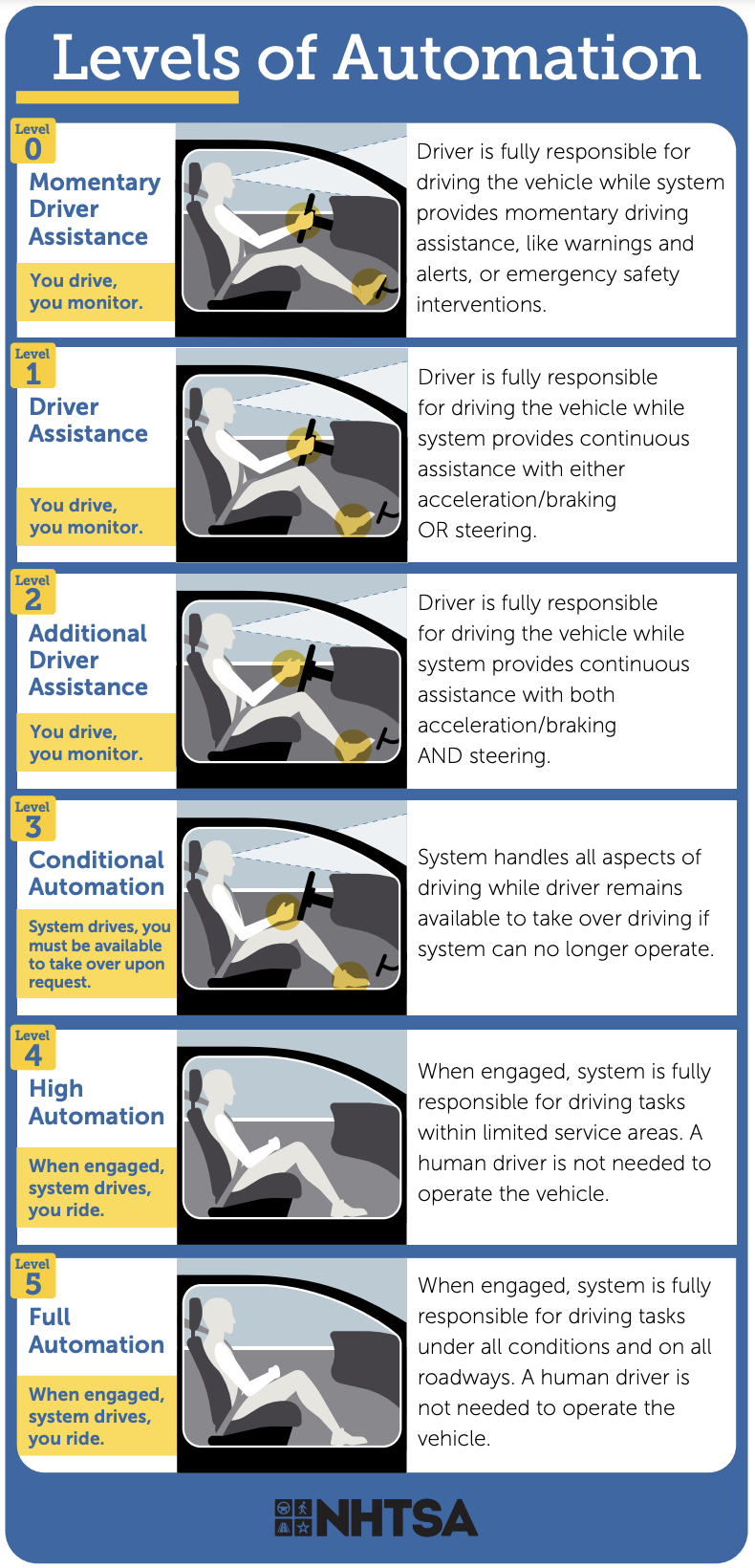

As time goes on and the models get better, gradually less human involvement will be necessary. Self-driving cars are a good metaphor here.

Right now, it feels like agents are operating at Level 2, maybe Level 3. They can automate some things, but a human still very much needs to be driving the bus. But as agents become smarter and more reliably, we’ll get to Level 4 and perhaps even FSD.

But even then, we’ll still want humans in the loop. No matter how reliable an AI assistant is, we’ll want it to periodically check in with us. We’ll want to know we can nudge it in the right direction if needed, just like we can with other humans.

Therefore the human in the loop is perhaps the most important design question for agents, but it’s often overlooked or treated as an afterthought. Most of the leading open source agent projects like AutoGPT, babyagi, and Crew AI don’t even have user interfaces and don’t make it easy for a human to intervene in the agent’s workflow.

Accommodating the human in the loop will require building new and better user interfaces for humans to see what agents are up to and intervene when necessary. It is primarily a design question, not an engineering question, and the space is still largely unexplored.

The graphical user interface unlocked the power of Software 1.0 by making it easy for average people to use. We have not yet found the graphical user interface for Software 2.0.

Memory

Software 2.0 systems will need a working memory of what's happened recently. Personal assistants must recall past conversations with the user. Workplace assistants need to know what’s happening around the company — what marketing campaigns are going on, the company's main products and key employees, and the company's brand.

Humans are constantly updating their memory. If you and I had a conversation, you'd expect me to remember it the next time we spoke. Unfortunately neural networks don't work this way. Every time you talk to ChatGPT, you're starting fresh. It will not remember its previous conversations with you.

This is because the neural network's weights do not update as it interacts with the world the way that the human brain's synapses constantly update. Updating a neural network's weights is quite slow and expensive, at least for now. To truly imbue neural networks with memory, we'd need a way to continuously update them, and research in this area — such as Geoff Hinton's Forward-Forward Algorithm — is still only in the very early stages.

The alternative to updating weights is to insert all the relevant information into the context window. This is called in-context learning. Instead of teaching the network about new concepts by training it and updating its weights, we instead feed the network relevant data at query time.

In this case, the application needs to insert all of the relevant information into the LLM's prompt every time it processes a new query. This can be improved by the usage of vector databases which can retrieve only the most semantically relevant "memories" or other context at query-time.

The length of context windows is currently a limiting factor, but context windows are rapidly expanding, with Google having recently released a 1 million token context window model. In a recent interview with Lex Fridman, Sam Atlman mused about "billion token" context windows that will contain "all of the information about our lives".

If that becomes a reality, that might be enough to imbue LLMs with superhuman memory. But still, how exactly this problem gets solved is an open question.

Just Plain Smarter

The last characteristic of the Software 2.0 systems of the future is that they’ll be a lot smarter than they are today. That might sound vague or obvious, but it’s worth reflecting for a moment on what it means and how far that trend will extend.

In 2020, Open AI released a paper in which they proved that LLMs got reliably, predictable smarter as they got larger. All the advancements in AI since then have borne this out. We have made models bigger and they’ve gotten steadily smarter.

“Smarter” is a fuzzy, unscientific term, but if you’ve used GPT 3, 3.5, and now 4, you’ll understand what this means. With each new generation, the model’s IQ simply seems to rise. They become more coherent. They can solve harder problems. They make fewer mistakes.

This is a really big deal, especially for agentic systems. The smarter the agents are, the bigger the tasks they can handle, and the less supervision they need. Today, agents are a cool toy but are often too brittle for production applications. But this won’t be the case for long.

A crucial question for builders and investors in AI is whether and when this trend will peter out. Can we continue to increase models’ intelligence indefinitely? Or is there some fundamental asymptote that we will brush up against, in the same way that we’ve begun reaching the limits of Moore’s law as transistors approach the size of atoms?

I personally suspect that this asymptote exists, and that it will be very difficult for AI to become smarter than the smartest humans in any domain, barring some new breakthrough. But I'd be happy to be proven wrong. And even if I'm right, having access to the intelligence of the smartest human on the planet in any particular domain for free, instantly, is extremely valuable and transformative.

Who will build it?

Finally, let’s preview the market landscape for the next era of software. Who will build the future of Software 2.0 and where will the value accrue?

I think the value chain will have three fundamental layers:

- Chips: The companies building the GPUs and TPUs on which all Software 2.0 runs. NVIDIA is by far the dominant player, with a virtual monopoly thanks to their CUDA toolkit.

- Foundation Models: The companies training LLMs and other very large models. There are roughly five key players here: Open AI, Anthropic, Mistral, Google, and Meta. Training models is very capital intensive, and it won't be something that many companies do.

- Applications: The companies who build applications on top of the foundation models that people use in their lives and their work. Some model providers will dabble in the application layer, especially for consumer apps like ChatGPT. But most applications will be built by new companies that don't exist yet or were only just born. Expect to see a cambrian explosion here over the coming years.

This isn’t so different from the market structure for Software 1.0 — you just have to replace model providers with operating systems.

| Software 1.0 1980 — 2020 | Software 2.0 2020 and beyond | |

|---|---|---|

| Chips |

|

|

Operating System / |

|

|

| Applications |

| To be created… |

Each of these three layers will overlap to a degree. For example, Google and Facebook are primarily model providers, but they are also endeavoring to build their own chips to lessen their dependence on Nvidia. Conversely, it wouldn't shock me if Nvidia dabbled in building their own LLMs.

But the more interesting overlap is between the model providers and the application layer. Many people are wondering where exactly the dividing line will fall here. There is a recurring meme of "Open AI Killed My Startup", where Open AI will release new developers like the Assistant API that render a whole class of startups obsolete.

Again, I think the history of Software 1.0 serves as a good metaphor here. As Apple and Microsoft pioneered the first personal computers, they cultivated a rich ecosystem of third party apps and invited developers to build applications that would work on their operating systems. However, they also built many basic applications themselves, like email clients, browsers, calendars, calculators, spreadsheets, slide decks, and word processors.

In some cases, third party apps would compete with OS-native applications. For example, in the browser market, Google Chrome and Mozilla Firefox compete with OS-native browsers like Internet Explorer, Safari, and Edge. But there were many lucrative categories of desktop software that Apple and Microsoft never competed with at all, like Adobe's digital publishing suite, video games, as well as a massive number of vertical, B2B apps.

A similar dynamic played out in mobile and cloud. iOS offered core applications like browsers, calendars, notes, email, etc., but also fostered a rich ecosystem of third party apps like Facebook, Instagram, AirBnB, Uber, Doordash, etc.

Cloud providers like AWS offer many low-level core services but also support a massive ecosystem of higher level services built on top of them. Often the lines between cooperation and competition are blurry, as with Dropbox or Vercel - services built on top of the cloud providers that also partially compete with their offerings.

I predict that the AI industry will settle on a similar dynamic of "coopetition", where the model providers offer some basic services on top of the foundation models, there are a handful of viable third-party competitors to those apps, and there are many more apps that the model providers don't compete with at all.

The Open AI Assistants API is a good example. This API makes it easy to build agents on top of Open AI's core models and equip them with memory and tools. I think it is likely that there will be a handful of startups that offer similar Agent APIs on top of the core LLMs. These startups won't build LLMs themselves, but instead will offer developer tooling on top of other LLMs.

I wouldn't necessarily want to be in this business myself, because it will mean competing with Open AI, Google, and other LLM providers. But I think there will be room for a few companies here apart from the model providers themselves, just as there has been room for a few web browsers apart from the ones offered by Microsoft and Apple.

The more ripe area, in my opinion, will be in highly verticalized software - both B2C and especially B2B — that the model providers have no desire to compete with at all. For example, I find it hard to imagine Open AI, Google, or Mistral ever building AI tailored to specific industries like medicine, law, education, e-commerce, or marketing. Instead, I foresee companies like Harvey AI or my own, Quotient, filling this gap.

I am tremendously excited by this area (which is after all why I quit my job to start an AI application startup). These applications are still in their infancy, which is why they are often pejoratively referred to as mere "GPT Wrappers" that provide relatively little value on top of the underlying models. But over time, they will become increasingly autonomous, more and more integrated with software 1.0 systems, imbued with memory, and just plain smarter.

Someday we'll look back and wonder how we ever went about our daily lives or ran our businesses without them. I can't wait to build that future.